Article originally written by Payam Fazli for http://Iranism.org on 21 Feb 2024

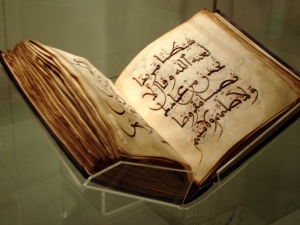

In the context of the 21st century, it is imperative that all texts purporting to offer ethical guidance, including religious scriptures, and in particular the Quran, are evaluated according to uniform ethical standards. This evaluation is crucial to ensure that these texts align with contemporary values and principles of human rights and dignity.

The reluctance of Islamic leadership within liberal societies to adapt or reinterpret the Quranic text so that it aligns with modern ethical norms presents a significant challenge to harmony and multiculturalism in modern society. In instances where religious authorities resist such necessary evolution, it becomes incumbent upon secular political leaders to advocate for and implement legislative measures that promote these essential changes including, but not limited to, revising and regulating the content of future versions of the Quran before publishing in the free world.

There is a pressing need to critically address and, where necessary, restrict the dissemination of specific Quranic verses deemed unethical or criminal by contemporary standards. This includes verses that may be interpreted to condone or incite crimes against humanity, war crimes, acts of violence such as rape and murder, and misogynistic behaviours, including the endorsement of violence against women.

To this end, if the publication of the Quran in societies that uphold freedom of speech and religion is to continue, it should be done with careful consideration of the content. Editions made available in these contexts should exclude or reinterpret verses that conflict with accepted ethical norms, ensuring that religious texts do not undermine the foundational values of equality, justice, and human welfare.

This approach should also extend to the regulation of Quranic texts imported into liberal democracies, as well as to the digital and physical copies utilised within mosques and other Islamic centres. By adopting a consistent and critical stance towards the ethical content of all religious texts, societies can better safeguard the principles of human rights and contribute to the cultivation of a more inclusive, respectful, and ethically coherent public discourse.

چکیده نوشتار به زبان پارسی:

در قرن بیست و یکم، همه متون اخلاقی، از جمله قرآن، باید بر اساس یک استاندارد اخلاقی یکسان و منطبق با اصول حقوق اساسی شهروندی قرن بیست و یکم قضاوت شوند. این نگاه یکسان و برابر برای هماهنگی با ارزشهای مدرن و حقوق بشر ضروری است. تردید رهبران جوامع اسلامی که در کشور های جهان آزاد زندگی می کنند در انطباق دادن قرآن با این استانداردهای اخلاقی قرن بیست و یکمی، چالشی برای همزیستی چندفرهنگی است.

نیاز به بازبینی انتقادی و محدودیت آیات قرآنی که غیراخلاقی تلقی میشوند وجود دارد. پیشنهاد میشود که سازمان های انتشاراتی که قرآن چاپ می کنند در جوامع آزاد باید محتوا را با دقت در نظر بگیرند، آیاتی که با هنجارهای اخلاقی در تضاد هستند را حذف یا مجدداً بازسازی کنند تا ارزشهای برابری، عدالت، و رفاه انسانی حفظ شود.

انتشار فیزیکی یا دیجیتال قرآن به شکل حاضر، چند فرهنگی را در جوامع سکولار به خطر می اندازد.

پیام فضلی ۲۱ فوریه ۲۰۲۴

Is the Quran a consistent text?

by Payam Fazli

MA English and Intercultural Studies – Allameh Tabataba’i University

Having been raised in Iran, the official education system under the Islamic regime indoctrinated the idea that the Quranic text is a ‘consistent’ text preserving its style throughout the Meccan and Medinan Surahs. As I grew fonder of linguistics, I realized the text, to the contrary of what Islamic scholar propose, cannot logically belong to one author.

Meccan vs. Medinan Surahs

Meccan Surahs:

These are generally shorter, with a focus on spiritual and ethical themes, including the oneness of God (Tawheed), the afterlife, judgment, and the stories of previous prophets. The style is often more poetic and characterized by vivid imagery and metaphors, aimed at appealing to the spiritual and moral consciousness of the listener. Some secular scholars speculate that these might have been works of poetry by the pre-Islamic poets that were later compiled by The Umayyad Caliphate.

Medinan Surahs:

Revealed after Muhammad’s alleged migration (Hijra) to Medina, these Surahs tend to be longer and deal more with social, legal, and political matters, reflecting the challenges and responsibilities of establishing an Islamic community and state. The content includes laws and regulations regarding family life, social justice, warfare, and community relations, among others. The tone turns bitter, darker and non-reconciliatory. Some independent linguistic speculations suggest that the authors of these parts are individually and anachronically separate entities.

The inconsistencies go overwhelmingly beyond the Meccan-Medinan dichotomy and unlike what the ‘Islamic scholars’ endeavour to ascertain from analyzing the Quranic text, in academic studies, the Quran is subjected to the same critical methods applied to any historical text. This includes textual criticism, historical analysis, and literary analysis, among others. These methods aim to understand the text’s origins, its compilation, and the context in which it was produced.

Academic perspectives on inconsistencies in the Quran vary, with some scholars arguing that these reflect the complex process of oral transmission, the context-specific nature of revelations, or editorial practices in the compilation of the text. Others view them as evidence of the text’s engagement with diverse religious, cultural, and social influences.

Attempting to address these inconsistencies within Islamic scholarship, Muslims resorted to the never-ending labyrinth of tafsir (exegesis) and hadith studies that seek to decipher and reconcile inconsistencies through various interpretive techniques, including abrogation (naskh), contextual analysis, and reference to the Prophet Muhammad’s life (sirah) and sayings (hadith).

Here I will provide an account of these inconsistencies from a secular, independent, non-Islamic and taqiyya-free perspective to the average reader. Albeit the reader must discern why the mainstream media and publications would not be very willing to publish or even discuss a view that defies the established Islamic claim that the Quran is a text produced by one author, let alone being sent down by a mythical entity from outside our solar system called “Allah”.

Identification of Inconsistencies

Textual Variability: Scholars examine the manuscript tradition of the Quran to identify variations in the text. While the Quranic text is remarkably stable compared to many other ancient texts, any textual tradition involves some degree of variation, which scholars study to understand the history of the text’s transmission.

Historical and Archaeological Analysis: This involves comparing Quranic narratives with historical and archaeological evidence. Inconsistencies might be identified when Quranic descriptions of historical events or practices differ from those found in contemporary non-Islamic sources.

Literary and Structural Analysis: Literary critics analyze the Quran’s structure, narrative techniques, and thematic organization. Inconsistencies or apparent contradictions within the text might be highlighted as part of its literary complexity. This includes exploring shifts in narrative voice, variations in the treatment of similar themes, or differences in legal and ethical injunctions.

Inter-textual Comparisons: The Quran is also studied in relation to earlier Jewish and Christian texts. Scholars look for parallels, borrowings, and divergences, which can reveal both the unique aspects of the Quranic message and its engagement with pre-existing religious traditions.

Examples of Inconsistencies

Narrative Discrepancies:

The story of Moses and Pharaoh is recounted multiple times throughout the Quran, with variations in detail that might be considered inconsistencies. For instance, the specifics of Moses’ conversations with Pharaoh and the signs he was given to perform vary across different Surahs (e.g., Surahs 7, 20, 26, 28).

Legal and Ethical Injunctions:

There are verses with differing instructions regarding the treatment of wives, including the process of arbitration and separation. For example, Surah 4:34 and Surah 2:228-232 offer guidance on marital relations and divorce, with scholars noting variations in the details of these processes.

The Quran’s stance on alcohol consumption shows a progression from allowance in moderation to a complete prohibition, reflecting a possible inconsistency or an example of gradual legislative revelation (e.g., Surah 2:219, Surah 4:43, Surah 5:90).

To give another example, the Quran frequently describes God (Allah) as “the Most Merciful, the Most Compassionate” (الرَّحْمَـٰنِ الرَّحِيمِ), emphasizing God’s forgiveness and mercy towards humanity. This theme is central to the Quran’s portrayal of the divine character and is meant to guide human behavior towards compassion and mercy. However, in an obnoxious turn of event the same merciful Allah in both Surah 4:24 and Surah 70:30 allows Muslim men to take women captive in wars, enslave and rape them. That comes with the Islamic assertion that the Quran is allegedly the direct word of Allah, as believed within the Islamic tradition.

When texts contain directives that conflict with established principles of human rights and dignity, they pose a profound ethical challenge at the level of genocide, war crimes or crimes against humanity that cannot be dismissed by appeals to divine authority or historical context. It should be condemned.

Theological Concepts:

The concept of God’s mercy and punishment can appear inconsistent, with some passages emphasizing unconditional forgiveness and others outlining strict retribution for disbelief or sin (e.g., Surah 7:156-157 vs. Surah 4:48).

Historical Anachronisms:

Critics have pointed to anachronisms in Quranic narratives, such as the mention of crucifixion in the story of Joseph (Surah 12), a method of execution not historically verified to have been used in Egypt at that time.

Conclusions and Societal Implications

When the Quran contains passages that sanction actions incompatible with axiomatic ethical norms of the free world—such as the enslavement of war captives and their sexual exploitation—it presents a stark threat to modern society as the followers of the text are firmly convinced that it is the very words of the Almighty applicable to all ages and contexts.

The Quran is understood to be conveying the direct commands of God, as it claims. Therefore, the directives such as those concerning war captives challenge modern conceptions of morality, which emphatically reject slavery and non-consensual sexual relations under any circumstances. Attributing such commands to a divine, morally perfect being is fundamentally at odds with contemporary ethical standards that prioritize human rights and individual autonomy.

As for Muslim apologists and left-leaning allies of Islamists who try to intellectualize the gravity of threats by resorting to Historical Contextualization fallacy, the argument that such commands were historically contingent and reflective of the norms of the 7th century does not mitigate the ethical issue from a secular perspective. Instead, it highlights the problem of considering a text as offering timeless moral guidance while containing directives that are ethically problematic by today’s standards.

I propose that any religious text, including the Quran, must be subject to the same ethical scrutiny as any other document proposing moral guidance in the 21st century. When texts contain directives that conflict with established principles of human rights and dignity, they not only pose a profound ethical challenge that cannot be dismissed by appeals to divine authority or historical context, but more dangerously the implications can extend beyond ethical challenges to potentially include social and security challenges as well. This is especially pertinent in diverse, multicultural societies where interpretations of religious texts might influence behavior and social policies in ways that affect communal harmony and security.

The free world must stop turning a blind eye to the axiomatic fact that interpretations of the currently publishable Quranic texts that advocate for violence or the mistreatment of others can contribute to radicalization and the justification of terrorist acts.

20/02/2024

Article originally written for http://Iranism.org

برگردان پارسی مقاله:

آیا قرآن متنی سازگار و یکدست است؟

در طول سال های زندگی در ایران، سیستم آموزشی رسمی تحت حکومت اسلامی، ایدهی سازگاری متن قرآنی را به ما القا می کرد که سبک خود را در سورههای مکی و مدنی حفظ میکند. همانطور که به زبانشناسی علاقهمند شدم، متوجه شدم که متن، برخلاف آنچه دانشمندان اسلامی پیشنهاد میدهند، منطقاً نمیتواند متعلق به یک نویسنده باشد.

سورههای مکی در مقابل سورههای مدنی

سورههای مکی: اینها معمولاً کوتاهتر هستند، با تمرکز بر موضوعات معنوی و اخلاقی، از جمله یگانگی خدا (توحید)، آخرت، داوری و داستانهای پیامبران قبلی. سبک آنها اغلب شاعرانهتر است و با تصاویر و استعارههای زنده مشخص میشود، با هدف جلب توجه به آگاهی معنوی و اخلاقی شنونده. برخی از دانشمندان سکولار حدس میزنند که اینها ممکن است آثار شعری توسط شاعران پیش از اسلام باشند که بعداً توسط خلافت اموی جمعآوری شدهاند.

سورههای مدنی: پس از مهاجرت ادعایی محمد به مدینه آشکار شدهاند، این سورهها معمولاً طولانیتر هستند و بیشتر با مسائل اجتماعی، قانونی و سیاسی سروکار دارند که چالشها و مسئولیتهای برپایی یک جامعه و دولت اسلامی را منعکس میکنند. محتوا شامل قوانین و مقررات مربوط به زندگی خانوادگی، عدالت اجتماعی، جنگ و روابط جامعه است. لحن تیرهتر، تلختر و غیر مصالحهجویانه میشود. برخی از گمانهزنیهای زبانشناختی مستقل پیشنهاد میکنند که نویسندگان این بخشها به طور جداگانه و ناهمزمان نهادهای جداگانهای هستند.

ناسازگاریها به شدت فراتر از دوگانگی مکی-مدنی میرود و برخلاف آنچه ‘دانشمندان اسلامی’ در تلاش برای اثبات از تحلیل متن قرآنی هستند، در مطالعات آکادمیک، قرآن مشمول همان روشهای نقدی میشود که به هر متن تاریخی اعمال میشود. این شامل نقد متنی، تحلیل تاریخی، و تحلیل ادبی است، در میان دیگران. این روشها با هدف درک منشأ متن، تدوین آن، و زمینهای که در آن تولید شده است، هستند.

دیدگاههای آکادمیک در مورد ناسازگاریها در قرآن متفاوت است، با برخی از دانشمندان استدلال میکنند که اینها منعکسکننده فرایند پیچیده انتقال شفاهی، ماهیت خاص زمینهای وحیها، یا شیوههای تحریری در تدوین متن است. دیگران آنها را به عنوان شواهدی از تعامل متن با تأثیرات مذهبی، فرهنگی و اجتماعی متفاوت میبینند.

در تلاش برای رسیدگی به این ناسازگاریها در علم کلام اسلامی، مسلمانان به دالان بیپایان تفسیر (تأویل) و مطالعات حدیث روی آوردند که سعی در رمزگشایی و سازگار کردن ناسازگاریها از طریق تکنیکهای تفسیری مختلف، از جمله نسخ، تحلیل زمینهای، و ارجاع به زندگی پیامبر محمد (سیره) و گفتارهای او (حدیث) دارند.

در اینجا حسابی از این ناسازگاریها از دیدگاهی سکولار، مستقل، غیر اسلامی و رها از تقیه که معمولاً مقاله های نویسنده های اسلامی به آن آغشته است به خواننده عادی ارائه میدهم.

هرچند خواننده باید درک کند که چرا رسانههای اصلی و انتشارات عمده جهان آزاد چندان مایل نیستند به انتشار یا حتی بحث در مورد دیدگاه های همچو منی که ادعای اسلام مبنی بر اینکه قرآن متنی تولید شده توسط یک نویسنده است را نمی پذیرم، چه رسد به اینکه در این نوشته، مطلقاً تحملی برای موجودی افسانهای که از خارج از منظومه شمسی نسخه ای برای انسان قرن بیست و یکم بپیچد وجود ندارد.

شناسایی ناسازگاریها:

تنوع متنی: دانشمندان با بررسی سنت نسخهبرداری قرآن به شناسایی تغییرات در متن میپردازند. در حالی که متن قرآنی نسبت به بسیاری از متون باستانی دیگر بسیار پایدار است، هر سنت متنی دارای برخی درجاتی از تغییر است که دانشمندان برای درک تاریخ انتقال متن آن را مطالعه میکنند.

تحلیل تاریخی و باستانشناسی: این شامل مقایسه روایات قرآنی با شواهد تاریخی و باستانشناسی است. ناسازگاریها ممکن است زمانی شناسایی شوند که توصیفات قرآنی از رویدادهای تاریخی یا شیوهها با آنچه در منابع غیر اسلامی معاصر یافت میشود، متفاوت باشد.

تحلیل ادبی و ساختاری: منتقدان ادبی ساختار قرآن، تکنیکهای روایی و سازماندهی موضوعی را تجزیه و تحلیل میکنند. ناسازگاریها یا تناقضات ظاهری در متن ممکن است به عنوان بخشی از پیچیدگی ادبی آن برجسته شوند. این شامل بررسی تغییرات در صدای روایی، تغییرات در درمان موضوعات مشابه یا تفاوتها در دستورات قانونی و اخلاقی است.

مقایسههای متنهای بینالمللی: قرآن همچنین در ارتباط با متون یهودی و مسیحی قبلی مطالعه میشود. دانشمندان به دنبال شباهتها، استقراضها و تفاوتها هستند که میتواند هم جنبههای منحصر به فرد پیام قرآنی و هم تعامل آن با سنتهای مذهبی قبلی را آشکار سازد.

مثالهایی از ناسازگاریها:

اختلافات روایی: داستان موسی و فرعون چندین بار در سراسر قرآن با تغییراتی در جزئیات که ممکن است به عنوان ناسازگاریها در نظر گرفته شوند، بازگو شده است. برای مثال، جزئیات گفتگوهای موسی با فرعون و نشانههایی که به او داده شده بود، در سورههای مختلف متفاوت است (به عنوان مثال، سورههای ۷، ۲۰، ۲۶، ۲۸).

دستورات قانونی و اخلاقی: آیاتی وجود دارد که دستورالعملهای متفاوتی در مورد درمان همسران، از جمله فرآیند داوری و جدایی ارائه میدهند. به عنوان مثال، سوره ۴:۳۴ و سوره ۲:۲۲۸-۲۳۲ راهنماییهایی در مورد روابط زناشویی و طلاق ارائه میدهند، که دانشمندان تغییراتی در جزئیات این فرآیندها را مشاهده میکنند.

موضع قرآن در مورد مصرف الکل نشاندهنده پیشرفتی از اجازه در حد اعتدال به ممنوعیت کامل است، که نشاندهنده یک ناسازگاری احتمالی یا مثالی از وحی تدریجی قانونگذاری است (به عنوان مثال، سوره ۲:۲۱۹، سوره ۴:۴۳، سوره ۵:۹۰).

برای مثال دیگر، قرآن به طور مکرر خدا (الله) را به عنوان “بخشنده مهربانترین” (الرَّحْمَـٰنِ الرَّحِیمِ) توصیف میکند که بخشش و رحمت خداوند به بشریت را تأکید میکند. این موضوع محوری در نمایش شخصیت الهی در قرآن است و قصد دارد رفتار انسان را به سمت رحمت و شفقت هدایت کند. با این حال، در تغییر ناگهانی رویداد، همان الله مهربان در هر دو سوره ۴:۲۴ و سوره ۷۰:۳۰ به مردان مسلمان اجازه میدهد زنان را در جنگها به اسارت و بردگی بگیرند و به آن ها تجاوز کنند. این با ادعای اسلامی مبنی بر اینکه قرآن مستقیماً کلام الله است، همانطور که در سنت اسلامی دقیقاً چنین باور دارند، همراه است.

وقتی متون مذهبی حاوی دستورالعملهایی هستند که با اصول تثبیت شده حقوق بشر و کرامت مغایرت دارند، آنها چالشی عمیق از نظر اخلاقی در سطح نسلکشی، جنایات جنگی یا جنایات علیه بشریت ایجاد میکنند که نمیتوان با استناد به اقتدار الهی یا زمینه تاریخی نادیده گرفت و باید یکصدا و قاطع محکوم شود.

مفاهیم الهیاتی: مفهوم رحمت و کیفر خدا میتواند ناسازگار به نظر برسد، با برخی آیات تأکید بر بخشش بیقید و شرط و دیگران ترسیم مجازات سخت برای کفر یا گناه (به عنوان مثال، سوره ۷:۱۵۶-۱۵۷ در مقابل سوره ۴:۴۸).

اناکرونیسمهای تاریخی: منتقدان به اناکرونیسمها در روایات قرآنی اشاره کردهاند، مانند ذکر صلب در داستان یوسف (سوره ۱۲)، روشی از اعدام که تاریخیاً تأیید نشده است که در مصر در آن زمان استفاده شده باشد.

نتیجهگیریها و پیامدهای اجتماعی

وقتی قرآن شامل متونی است که اقدامات ناسازگار با هنجارهای اخلاقی بدیهی جهان آزاد—مانند اسارت افراد جنگی و سوءاستفاده جنسی از آنها—را تأیید میکند، تهدیدی آشکار برای جامعه مدرن ایجاد میکند زیرا پیروان متن به شدت معتقدند که این دقیقاً کلمات خداوند است که برای تمام دورانها و زمینهها قابل اجرا است.

قرآن به عنوان فرمانهای مستقیم خداوند، همانطور که ادعا میکند، درک میشود. بنابراین، دستورالعملهایی مانند آنهایی که به موضوع اسیران جنگی مربوط میشوند، مفاهیم مدرن اخلاق را به چالش میکشند، که به شدت بردگی و روابط جنسی غیر رضایتی را رد میکنند. نسبت دادن چنین فرامینی به یک موجود کاملاً اخلاقی با استانداردهای اخلاقی معاصر که بر حقوق بشر و استقلال فردی تأکید دارند، به طور بنیادی ناسازگار است.

دست و پا زدن های مدافعان اسلام و متحدان چپگرای اسلامگرایان که تلاش میکنند با استناد به مغالطه توسل به شرایط تاریخی، وزن تهدیدات را سبک کنند و مثلاً بیان میکنند که این فرامین مربوط به دوره تاریخی دیگری است و بازتابدهنده هنجارهای قرن هفتم، مسئله را از دیدگاه سکولار حل نمیکند. بلکه، مشکلی را نشان میدهد که یک متن به عنوان راهنمایی اخلاقی بیزمان در نظر گرفته شود در حالی که دستورالعملهایی دارد که از نظر اخلاقی با استانداردهای امروزی مشکلدار است.

من پیشنهاد میکنم که هر متن مذهبی، از جمله قرآن، باید مشمول همان بررسی اخلاقی به عنوان هر سند دیگری که راهنمایی اخلاقی در قرن بیست و یکم را پیشنهاد میدهد، باشد. وقتی متون حاوی دستورالعملهایی هستند که با اصول تثبیت شده حقوق بشر و کرامت در تضاد هستند، نه تنها چالشی عمیق از نظر اخلاقی ایجاد میکنند که نمیتوان با استناد به اقتدار الهی یا زمینه تاریخی نادیده گرفت، بلکه عواقب آن میتواند فراتر از چالشهای اخلاقی به چالشهای اجتماعی و امنیتی نیز گسترش یابد. این بهویژه در جوامع چندفرهنگی که تفسیرهای متون مذهبی ممکن است رفتار و سیاستهای اجتماعی را به روشهایی تحت تأثیر قرار دهد که بر هماهنگی جامعه و امنیت تأثیر میگذارد، مرتبط است.

جهان آزاد نباید این واقعیت بدیهی را دائماً نادیده بگیرد که متون قرآنی کنونی خشونت یا بدرفتاری با دیگران را ترغیب میکند و میتواند به رادیکالیزه شدن و توجیه اعمال تروریستی کمک کند.